Why, and how, investors might consider integrating biodiversity into fixed income portfolios

- 14 April 2023 (7 min read)

Key points:

- Managing risks, potential for positive impact, and meeting regulations are three reasons fixed income investors should consider biodiversity within their portfolios

- Biodiversity loss is a complex issue – it requires active engagement and detailed sector- and issuer-level analysis

- Biodiversity must be considered as part of a holistic sustainable approach, as opposed to in isolation to climate change and social factors

One of the fundamental features of biodiversity is that it pervades every part of our lives – and that means its impacts are felt across investment portfolios, too. In our view, all asset classes and sectors would benefit from close consideration of how biodiversity loss might change outcomes or affect financial returns.

When we look specifically at fixed income, we see important reasons why investors should begin to integrate biodiversity into their decision making.

First, biodiversity loss presents risks that could potentially impact the performance of fixed income portfolios. As with climate change, we must first understand the risks at play, divided into two components. First are physical risks from biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation, and second are transition risks linked to global efforts to tackle the problem, which include increasing liability risks.

We expect companies which do not proactively address these risks – and fail to adopt more sustainable nature-positive business models – could face higher costs or lower revenues, therefore reducing their ability to repay debt in the future.

- Nature-related physical risks: The dramatic degradation of biodiversity and natural resources has created significant pressures on issuer supply chains and manufacturing processes and will continue to do so unless addressed. In turn, this may lead to a revenue loss or reduced profitability, ultimately impairing an issuer’s ability to repay its debt. Examples include increased flood risks due to soil and flora reductions, difficulties sourcing raw materials, reduced suitability of land for crop cultivation, or costs incurred from forced manufacturing base relocations.1

- For instance, the nuclear sector and the paper industry are responsible for large-scale water withdrawal and often position their operations near water sources. Further, many new nuclear facilities are built close to the sea, but existing inland sites will likely face water stress risks at some level. Over time, water availability may become a real operational risk for these industries.

-

Nature-related transition risks: Consumers are becoming more aware of the dangers of biodiversity loss and may shift their spending habits to companies and issuers with theproducts and services least associated with negative impacts on nature. The shift could be more acute in the face of controversial events, such as wide consumer bases boycotting a company’s products. In addition, issuers could face further risks from evolving regulation, technological breakthroughs, market changes, and litigation.

A good example of liability-related transition risks with US litigation around perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) i.e., a large complex set of synthetic chemicals used in consumer goods. This litigation has given rise to new regulatory measures in both the US and European Union with a potential ban targeting these so-called ”forever chemicals”. Another recent example is the introduction of taxes on plastic packaging in some countries – like the UK – seeking to encourage intensive plastic users to adapt the company’s business model.2

In our view, interactions between different categories of nature-related risks, particularly cascading interactions of physical and transition risks, could eventually lead to a nature-related systemic risk with consequences for global economies.

Asset owners: The momentum builds

A second reason we believe fixed income investors need to take action is the increasing interest we’re seeing from asset owners looking to mitigate their negative impact by reducing their investment and financing activities’ biodiversity footprint. This rationale extends beyond pure financial performance ”double materiality” – i.e., investors should consider not only the impact the external environment has on a portfolio, but also the impact a portfolio has on the natural and social capital in the world.

This process can occur in two ways – by reducing the negative impact a portfolio has or by identifying and supporting nature-positive solutions with the potential to drive change within different sectors.

Data indicates between $150bn-$440bn per year should be allocated to biodiversity solutions to reverse biodiversity loss.3 However, we believe the private sector’s current financial flows are merely a drop in the ocean. Estimates indicate that in 2020 only between $78bn-$91bn was invested in biodiversity solutions, with the large bulk from public financing.4 Clearly there is more work to do and harnessing the scale of financial markets can contribute to plug the gap. Fixed income’s size and pervasiveness can create meaningful change, potentially driving issuers to reduce their biodiversity footprints.

(More) regulations are on the way

Established in 2021, the Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) aims to factor biodiversity into financial and business decisions by creating a framework for disclosure and for assessing risks, impacts, opportunities, and dependencies. The TNFD plans to finalize its complete recommendations by September 2023 and center them around the same four pillars as its existing Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD): governance, strategy, risk and impact management, and metrics and targets.

Thankfully, many investors will have already digested TCFD’s requirements and apply a similar framework regarding biodiversity and implementing TNFD guidancecan leverage on their experience implementing TCFD’s requirements when considering biodiversity and applying the TNFD framework. While the risks, metrics, and targets may be different, the learnings around access to data and implementation within portfolios can be applied with similar governance frameworks. We believe, like the TCFD, the escalation of TNFD-adoption may quickly filter through to mandatory reporting for many investors, necessitating greater understanding of the topic among all investors.

These are the three drivers putting biodiversity center stage: The risks are becoming ever more evident; large asset owners are starting to measure their impact and consider how to adapt portfolios; and approaching regulatory demands are spurring the process. The next question: How can fixed income managers successfully integrate biodiversity into portfolios?

Assessing portfolio risks and impacts

The extent to which fixed income investors can consider biodiversity is determined by the availability of information from which they can make credible portfolio decisions. Data availability, quality, and coverage are all crucial, as is what the data aims to show (e.g., risks to the portfolio, impacts of the portfolio, or alignment to future nature-related goals). As it stands, biodiversity data isn’t perfect. Rather than waiting for improved data, however, portfolio-level decisions should consider accommodating what exists to kickstart integration.

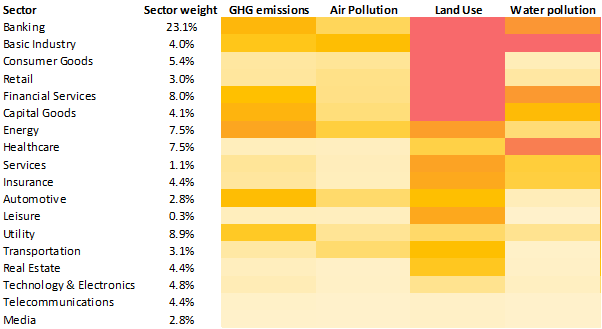

The heatmap below shows four of the primary drivers of biodiversity loss across the global investment-grade credit sectors, as measured with the use of the Corporate Biodiversity Footprint (CBF) metric provided by Iceberg Data Lab.5 The CBF is expressed in square kilometres (km2) of mean species abundance (MSA) – a recognized proxy for the intactness of biodiversity compared to a pristine, undisturbed state. For example, a CBF of -0.2km2 MSA would tell us that the pressures generated by a company’s activities during a given year are estimated to have degraded entirely the biodiversity of an area equivalent to 200m2.

- PGEgaHJlZj0iaHR0cHM6Ly9mcmFtZXdvcmsudG5mZC5nbG9iYWwvZnJhbWV3b3JrLWFuZC1ndWlkYW5jZS9jb25jZXB0cy1hbmQtZGVmaW5pdGlvbnMvZGVmaW5pdGlvbnMtb2Ytcmlza3MvIj5UYXNrZm9yY2Ugb24gTmF0dXJlLXJlbGF0ZWQgRmluYW5jaWFsIERpc2Nsb3N1cmVzICgzLzIwMjMpOiBUTkZE4oCZcyBkZWZpbml0aW9ucyBvZiByaXNrczwvYT4=

- e2h0dHBzOi8vd3d3Lmdvdi51ay9ndWlkYW5jZS9jaGVjay1pZi15b3UtbmVlZC10by1yZWdpc3Rlci1mb3ItcGxhc3RpYy1wYWNrYWdpbmctdGF4Izp+OnRleHQ9UGFja2FnaW5nJTIwc2hvdWxkJTIwb25seSUyMGNvbnRhaW4lMjByZWN5Y2xlZCxvZiUyMCVDMiVBMzIwMCUyMHBlciUyMHRvbm5lLjtVbml0ZWQgS2luZ2RvbSBITSBSZXZlbnVlICZhbXA7IEN1c3RvbXMgKDMvMzEvMjAyMyk6IFBsYXN0aWMgUGFja2FnaW5nIFRheDogc3RlcHMgdG8gdGFrZX0=

- PGEgaHJlZj0iaHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuY2JkLmludC9maW5hbmNpYWwvaGxwL2RvYy9obHAtMDItcmVwb3J0LWVuLnBkZiI+Q29udmVudGlvbiBvbiBCaW9sb2dpY2FsIERpdmVyc2l0eSAoMjAxNCk6IFJlc291cmNpbmcgdGhlIEFpY2hpIEJpb2RpdmVyc2l0eSBUYXJnZXRzOiBBbiBBc3Nlc3NtZW50IG9mIEJlbmVmaXRzLCBJbnZlc3RtZW50cyBhbmQgUmVzb3VyY2UgbmVlZHMgZm9yIEltcGxlbWVudGluZyB0aGUgU3RyYXRlZ2ljIFBsYW4gZm9yIEJpb2RpdmVyc2l0eSAyMDExLTIwMjA7IFNlY29uZCBSZXBvcnQgb2YgdGhlIEhpZ2gtTGV2ZWwgUGFuZWwgb24gR2xvYmFsIEFzc2Vzc21lbnQgb2YgUmVzb3VyY2VzIGZvciBJbXBsZW1lbnRpbmcgdGhlIFN0cmF0ZWdpYyBQbGFuIGZvciBCaW9kaXZlcnNpdHkgMjAxMS0yMDIwPC9hPg==

- PGEgaHJlZj0iaHR0cHM6Ly93d3cub21maWYub3JnL3dwLWNvbnRlbnQvdXBsb2Fkcy8yMDIwLzEyL1NQSV9KTkxfMTIucGRmP3V0bV9zb3VyY2U9b21maWZ1cGRhdGUmYW1wIj51dG1fY2FtcGFpZ249b21maWZ1cGRhdGU7T01GSUYgU3VzdGFpbmFibGUgUG9saWN5IEluc3RpdHV0ZSBKb3VybmFsIChEZWNlbWJlciAyMDIwKTogVGltZSB0byBhbGlnbiBmaW5hbmNlIHdpdGggYmlvZGl2ZXJzaXR5IG9iamVjdGl2ZXM8L2E+

- QVhBIElNIGlzIGEgc2hhcmVob2xkZXIgaW4gSWNlYmVyZyBEYXRhIExhYi4=

Picking out the biodiversity hotspots

Source: Iceberg Data Lab. Data as of 12/31/2022. For ease of illustration the CBF has been translated into a colour scale with the most impactful (red) having a score of -0.2km2 MSA per million euros invested while the least impactful (light orange) having an MSA closer to zero.

One of the most striking findings is how heavily land use change contributes to overall biodiversity loss. Scientific consensus has identifying these changes as the main pressure on biodiversity.6 As such, it presents a key focus area in terms of minimizing footprint and developing solutions. Another notable finding is the prominence of banking and financial services, perhaps a surprise given the sectors’ relatively low indirect emissionsthese sectors are usually associated with smaller footprints in carbon emissions, at least from their direct operations. HoweverHowever, Scope 3 considers indirect, biodiversity impacts as part of the CBF metric.7 As with carbon emissions data, the CBF data driving this exercise shows there is a clear skew in the impact between different sectors, something worth considering when integrating biodiversity into fixed income portfolios.8

Biodiversity’s investment potential

After seeking the portfolio ”hotspots” across sectors and specific issuers, investors can begin re-aligning their portfolios to reflect best practices in biodiversity integration.

One starting point is tilting portfolios away from issuers with high biodiversity footprints and little ambition to reduce it toward companies in the same sector that have identified the risks and impacts are managing andmanaging and monitoring them. Detailed issuer-level analysis is critical to assess the ambition and credibility of any corporate objectives.

We think fixed income investors can also use the lever of bond maturities to mitigate biodiversity-related risks within their portfolios. For example, issuers with high dependencies on natural resources or high biodiversity footprints may invest in shorter maturities and only re-invest upon maturity if the associated issuers have sufficiently committed to mitigating those risks or lower their footprints.

But what about managing this process of making changes to fixed income portfolios? While all investors can use portfolio inflows – and outflows – and active turnover to re-shape their strategies, fixed income investors also benefit from a certain portion of their portfolio maturing each year – often as much as 25% in short duration strategies. This natural turnover may present portfolio managers with the opportunity to re-invest the proceeds to achieve their biodiversity goals in a cost-efficient manner and re-align their strategies to biodiversity integration’s best practices.

The upcoming release of science-based pathways and sectoral guidelines – namely those expected from the Science Based Targets Network (SBTN) – should further enhance the corporates and investors’ ability to integrate biodiversity into their decision-making process.9 But ultimately, clients’ objectives will drive how asset managers integrate and re-align portfolios to take biodiversity into consideration. This makes active collaboration, education, and knowledge-sharing with clients central to ensuring they fully understand the issues around biodiversity loss and natural capital degradation.

Engaging with key sectors and issuers

Having a constructive dialogue and actively encouraging issuers to shift their business practices to reduce their biodiversity footprint is a key method to foster positive change. From a financial perspective, it helps identify those ”hotspots” within a portfolio and structure discussions with issuers around material nature-related topics – helping them become more aware of, and resilient to, the implications of supply chain and consumer risks from biodiversity loss. In other words, helping them avoid any surprises that might impair their ability to repay debt.

From an impact perspective, this dialogue should encourage sustainable investors to take their share of responsibility by working closely with the investee companies to foster systemic change and protect natural capital.

- PGEgaHJlZj0iaHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuaXBiZXMubmV0L2dsb2JhbC1hc3Nlc3NtZW50Ij5JUEJFUyAoNS8yMDE5KTogR2xvYmFsIEFzc2Vzc21lbnQgUmVwb3J0IG9uIEJpb2RpdmVyc2l0eSBhbmQgRWNvc3lzdGVtIFNlcnZpY2VzOiBGb3IgdGVycmVzdHJpYWwgYW5kIGZyZXNod2F0ZXIgZWNvc3lzdGVtcywgbGFuZC11c2UgY2hhbmdlIGhhcyBoYWQgdGhlIGxhcmdlc3QgcmVsYXRpdmUgbmVnYXRpdmUgaW1wYWN0IG9uIG5hdHVyZSBzaW5jZSAxOTcwLCBmb2xsb3dlZCBieSB0aGUgZGlyZWN0IGV4cGxvaXRhdGlvbiwgaW4gcGFydGljdWxhciBvdmVyZXhwbG9pdGF0aW9uLCBvZiBhbmltYWxzLCBwbGFudHMsIGFuZCBvdGhlciBvcmdhbmlzbXMsIG1haW5seSB2aWEgaGFydmVzdGluZywgbG9nZ2luZywgaHVudGluZywgYW5kIGZpc2hpbmcuIEluIG1hcmluZSBlY29zeXN0ZW1zLCB0aGUgbGFyZ2VzdCBpbXBhY3QgaGFzIGNvbWUgZnJvbSBkaXJlY3QgZXhwbG9pdGF0aW9uIG9mIG9yZ2FuaXNtcyAobWFpbmx5IGZpc2hpbmcpIGltcGFjdCwgZm9sbG93ZWQgYnkgbGFuZC0gYW5kIHNlYS11c2UgY2hhbmdlIDwvYT4=

- U2NvcGVzIDEgYW5kIDIgcmVmZXIgdG8gZGlyZWN0IGltcGFjdHMgZnJvbSBhIGNvbXBhbnnigJlzIG93biBvcGVyYXRpb25zIHdoaWxlIHNjb3BlIDMgY292ZXJzIGluZGlyZWN0IGltcGFjdHMsIHdoZXRoZXIgZnJvbSBzdXBwbHkgY2hhaW5zLCByYXcgbWF0ZXJpYWxzIHVzZSwgb3IgY29uc3VtZXIgYmVoYXZpb3IuIEZvciB0aGUgZmluYW5jaWFsIHNlY3RvciwgU2NvcGUgMyBpbmNvcnBvcmF0ZXMgZmluYW5jaW5nIGFuZCBpbnZlc3RtZW50IGFjdGl2aXRpZXMu

- Q0JGIGRhdGEgaXMgY3VycmVudGx5IGFsbW9zdCBlbnRpcmVseSBtb2RlbGVkIGFuZCBpbnRlZ3JhdGVzIG9ubHkgc29tZSBvZiB0aGUgZml2ZSBwcmltYXJ5IGRyaXZlcnMgb2YgYmlvZGl2ZXJzaXR5IGxvc3MgYXMgZGVmaW5lZCBieSBJUEJFUy4gSXQgdGhlcmVmb3JlIHByb3ZpZGVzIGEgcGFydGlhbCBwaWN0dXJlIG9mIGVmZmVjdGl2ZSBpbXBhY3RzIGFuZCByaXNrcy4gVGhlIGRhdGEgYW5kIG1vZGVsIGNvbnRpbnVlIHRvIGV2b2x2ZS4=

- U2NpZW5jZSBCYXNlZCBUYXJnZXRzIE5ldHdvcmsgKDMvMjAyMyk6IE91ciBtaXNzaW9u

CASE STUDY – Biodiversity-specific projects in green bonds

Most bonds finance issuers’ general operating and capital expenditures. But use-of-proceeds bonds such as green, social, and sustainability bonds can be directly linked to projects contributing to environmental or social objectives. There are currently no explicit ”biodiversity” bonds; however, several green bonds nod toward biodiversity. Estimates indicate at least 15% of green sustainable debt use of proceeds under analysis went to the land use, water, and waste project categories in 2021.10

The report also shows a slow but positive increase in land use project financing since 2014. AXA IM internal research comes to the same conclusions as regards the sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) market, with 15%-18% of all the SLBs analysed in 2022 integrating nature-related targets, most of them focused on waste and water management.

In the current absence of clear trajectories on biodiversity, companies prefer to issue climate-oriented green bonds; therefore, a lot of nature-related use-of-proceeds bonds issuance comes from sovereign issuers.

Integrating biodiversity considerations into fixed income can be achieved through a range of tools and selecting green bonds with explicit biodiversity objectives as part of a wider green or traditional bond portfolio could materially contribute to this objective.

It is important to center engagement around the sectors and issuers most relevant to the challenge at hand (see the hotspots graphic above). As with climate change, engagement on biodiversity loss can extend from individual dialogue with companies to participation in collaborative initiatives such as Nature Action 100,11 to expressing convictions through public policy consultations and beyond. Indeed, global collective action is important to achieve real, specific issuer-level and system-wide impact in terms of biodiversity protection and manage properly nature-related risks and opportunities for investment portfolios.

In some cases of engagement, it’s possible an issuer may be resistant to changing its business practices, perhaps in fear of reducing profitability in the short run. Here a clear and established engagement framework and escalation process – which in extreme cases can even result in divestment – is critical to monitoring and implementing actions based on engagement activities.

Some might see divestment as the quickest way to reduce a portfolio’s biodiversity footprint, but it can have a counter-effect to a comprehensive and effective engagement strategy. In short, divestment means reducing the investible universe and extinguishing the point of contact and the potential leverage over the issuer. With biodiversity-related data still maturing and financial institutions still building knowledge on the topic, an active engagement strategy for effectively tackling nature-related risks and identifying opportunities may be better adapted than divestment o the whole.

- PGEgaHJlZj0iaHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuY2xpbWF0ZWJvbmRzLm5ldC9yZXNvdXJjZXMvcmVwb3J0cy9zdXN0YWluYWJsZS1kZWJ0LWdsb2JhbC1zdGF0ZS1tYXJrZXQtMjAyMSI+Q2xpbWF0ZSBCb25kcyBJbml0aWF0aXZlICg0LzE5LzIwMjIpOiBTdXN0YWluYWJsZSBEZWJ0IEdsb2JhbCBTdGF0ZSBvZiB0aGUgTWFya2V0IDIwMjE8L2E+

- e2h0dHBzOi8vd3d3LmlpZ2NjLm9yZy9uZXdzL2F0LWNvcDE1LWludmVzdG9ycy1hbm5vdW5jZS1uYXR1cmUtYWN0aW9uLTEwMC10by10YWNrbGUtbmF0dXJlLWxvc3MtYW5kLWJpb2RpdmVyc2l0eS1kZWNsaW5lLyM6fjp0ZXh0PU5hdHVyZSUyMEFjdGlvbiUyMDEwMCUyMGlzJTIwYSxhbmQlMjBiaW9kaXZlcnNpdHklMjBsb3NzJTIwYnklMjAyMDMwLjtJbnN0aXR1dGlvbmFsIEludmVzdG9ycyBHcm91cCBvbiBDbGltYXRlIENoYW5nZSAoMTIvMTEvMjAyMik6IEF0IENPUDE1LCBpbnZlc3RvcnMgYW5ub3VuY2UgTmF0dXJlIEFjdGlvbiAxMDAgdG8gdGFja2xlIG5hdHVyZSBsb3NzIGFuZCBiaW9kaXZlcnNpdHkgZGVjbGluZX0=

Where does biodiversity fit in relation to other sustainable investing?

Climate, biodiversity, and social factors are inextricably linked. There is little value in pursuing improvements in one at the expense of others. There are clear connections, for example, between climate change and biodiversity:

- Climate change is one of the five direct drivers of biodiversity loss – limiting climate change is therefore part of the solution for mitigation biodiversity erosion.

- Natural capital and nature-based solutions – such as mangroves and forestry – not only represent high biodiversity-value areas but are also perfect carbon sinks which can help offset human-made carbon emissions.

- Some climate change solutions may have important biodiversity impacts and contribute to biodiversity degradation. Take the building of a new dam as an example. While providing clean energy, it usually has significant impact on the surrounding biodiversity ecosystems.

A holistic assessment of environmental risks is therefore key for an effective transition to more sustainable economies.

When integrating climate change into investments, we think undertaking a full lifecycle and value-chain analysis is essential when considering the biodiversity loss and social impacts . In general, the fundamental analysis undertaken should, at a minimum, be based on a “do no significant harm” principle. This will enable positive progress in each key area without damaging another.

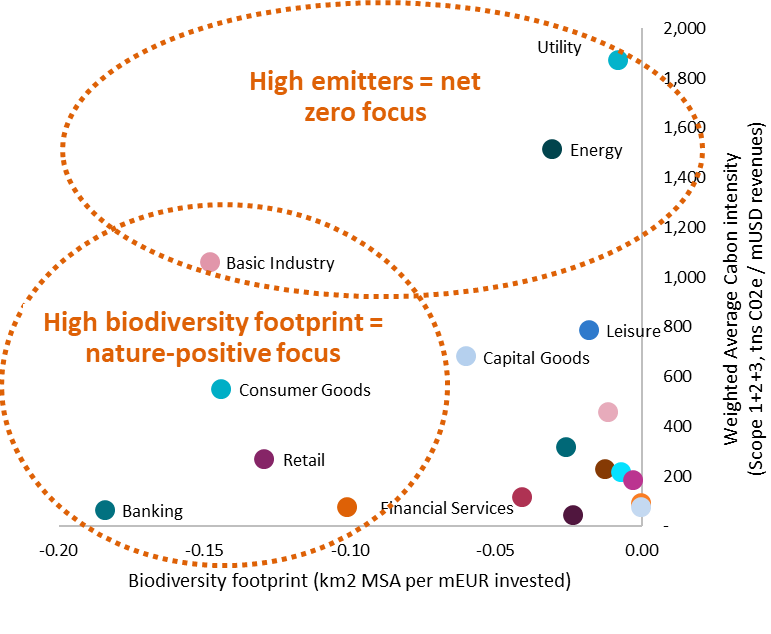

The chart below shows the correlation between the weighted average carbon intensity (WACI) and biodiversity footprint (excluding climate change) across the global investment grade credit sectors.

The correlation between biodiversity loss and carbon emissions

Source: AXA IM, Trucost, Iceberg Data Lab, 12/31/2022

Clearly some sectors – such as basic industry – must tackle the climate change and biodiversity crises together, while others can focus on one or other (e.g., utilities and climate change or consumer goods and biodiversity), while still applying safeguards to avoid lateral environmental consequences.12

In the same way investors need to prepare for and consider a “just transition” weighing social impacts on the path to net zero, biodiversity loss is another factor that must not suffer from investors’ carbon “tunnel vision.”

Fixed income investors can make a difference now

Biodiversity loss is rapidly rising on investors’ agendas due to the potential risks it can pose to their portfolios, the impact their investments have on the world, and to prepare for upcoming regulations.

As a massive source of liquid capital, fixed income investors have a sizeable part to play in this emerging theme and can take steps to actively improve their portfolios’ biodiversity footprints. We find the running theme across implementation options requires analysis to consider the full breadth of available data but ultimately driven by name and sector-specific fundamental analyses. This allows investors to:

- Build internal knowledge and expertise on the biodiversity topic

- Identify and properly manage nature-related impacts, dependencies, risks, and opportunities

- Determine the most appropriate engagement agenda and escalation tactics

In turn, we think investors can efficiently integrate biodiversity – and climate – into their portfolios, potentially avoiding negative impact on performance and positively contributing to returns while delivering long-term benefits to economies and people across the world.

- Q0JGIGRhdGEgaXMgY3VycmVudGx5IGFsbW9zdCBlbnRpcmVseSBtb2RlbGVkIGFuZCBpbnRlZ3JhdGVzIG9ubHkgc29tZSBvZiB0aGUgZml2ZSBwcmltYXJ5IGRyaXZlcnMgb2YgYmlvZGl2ZXJzaXR5IGxvc3MgYXMgZGVmaW5lZCBieSBJUEJFUy4gSXQgdGhlcmVmb3JlIHByb3ZpZGVzIGEgcGFydGlhbCBwaWN0dXJlIG9mIGVmZmVjdGl2ZSBpbXBhY3RzIGFuZCByaXNrcy4gVGhlIGRhdGEgYW5kIG1vZGVsIGNvbnRpbnVlIHRvIGV2b2x2ZS4=