Understanding scope 3: How responsible investors can wrestle with the unruliest of emissions

- 23 February 2023 (7 min read)

Key points:

- A company’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are often referred to as either scope 1, scope 2 or scope 3. The first of these refers to direct emissions from a company’s activity and the second to emissions related to operational electricity use

- A company’s scope 3 emissions are those found along its value chain, both upstream (before) and downstream (after) its own operations

- The availability, quality, and reliability of scope 3 data are a concern, but a diminishing one, and regulation will help

- In aggregate, scope 3 emissions account for 79% of total emissions. Two-thirds of scope 3 (hence half of total emissions) come from the use of products. This means reducing scope 3 will mostly be achieved by changing products or by changing demand dynamics

- In some sectors more reliant on fossil fuels, a truly net zero scope 3 would mean entirely phasing out current products or fully reengineering them

- AXA IM is committed to net zero and wants investee companies to include scope 3 in their climate reporting. However, we think it is understandable if this is not fully realized at this point, given the challenges of adapting complex value chains, including elements outside of a company’s control

On one level, it is easy to understand the scale of emissions from a company’s operations. If a factory is pumping out millions of plastic widgets, we can measure the greenhouse gases (GHGs) produced as it does so and the emissions linked to the energy used to make them. However, things can get a little murkier when we look up or down the value chain, perhaps at the customers putting their shiny new widget to use in the real world.

As responsible investors seek to align portfolios with their own climate ambitions and more broadly to the global push towards net zero, understanding that more nuanced side of the emissions calculation is becoming ever more important – and ever more possible. We call these indirect emissions “scope 3,” and they fit into a long-established model for categorizing the GHGs that leak into our atmosphere.

Defining “scopes”

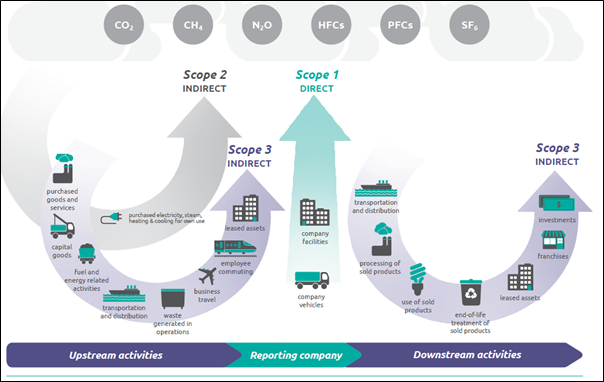

The main standard for measuring and reporting emissions comes from the Greenhouse Gas Protocol.1 Emissions are classified in three buckets or “scopes” :2

- Scope 1: Direct emissions from company-owned or company-controlled sources

- Scope 2: Indirect emissions from the generation of purchased energy consumed by the company. Practically, it mostly relates to the purchase of electricity and heat

- Scope 3: All other indirect emissions that occur in a company’s value chain. Scope 3 is further broken down into two broad categories – upstream for activities before the company’s own operations and downstream for activities after. Altogether there are 15 sub-categories within scope 3.

Presented slightly differently, you might think of scope 2 as the scope 1 of a company’s electricity suppliers. Scope 3 can then be thought of as the scope 1 and 2 of the suppliers, partners, and customers interacting with the products and services a company delivers.

Understanding the importance and challenges of scope 3 emissions has become a growing concern for large investors who often have their own net zero targets to consider. Investors, as companies, are increasingly being asked – and indeed will be regulatorily obliged – to include scope 3 in their energy transition strategies. Properly understanding the implications is critical to them.

Exhibit 1: Emission scopes and value chain

Source: Greenhouse Gas Protocol

Emissions in numbers

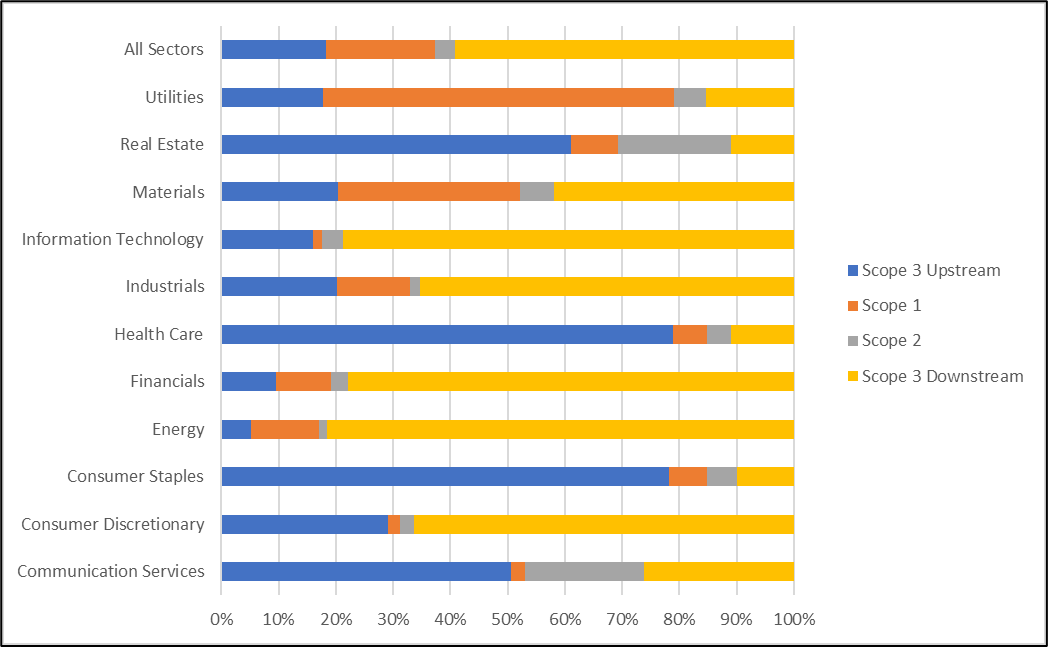

So, how do these emissions stack up against each other? The following charts, derived from data provided by the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), presents the emissions from 5,364 companies – commercial, industrial, and financials – for the year 2019.3 It is a mix of reported and estimated (mostly for scope 3) numbers. Scope 1 GHG emissions in this database are 13.8 gigatons (GT). That equates to 27.7% of global emissions, according to the World Resources Institute, which put total 2019 emissions at about 49.8GT.4

We collated the data by sectors, using Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS) definitions, and by scope, separating upstream and downstream scope 3. The results are shown first on a repartition basis (Exhibit 2), then in absolute (Exhibit 3).

One immediate observation is that scope 3 emissions dominate as they account for a massive 79% of total emissions, of which 59% is downstream.

There are exceptions as always. If we drill down in more detail to industry level, we find that out of 69 industry categories, seven have scope 1 and 2 representing more than half of total emissions: Paper and forest products, shipping, independent power producers, electric utilities, airlines, cement producers, and water utilities. When engaging with companies from those industries, the focus should be on direct emissions.

Exhibit 2: Breakdown of emissions by scope and by sector

Source: CDP 2019: Full GHG Emissions Dataset, AXA IM

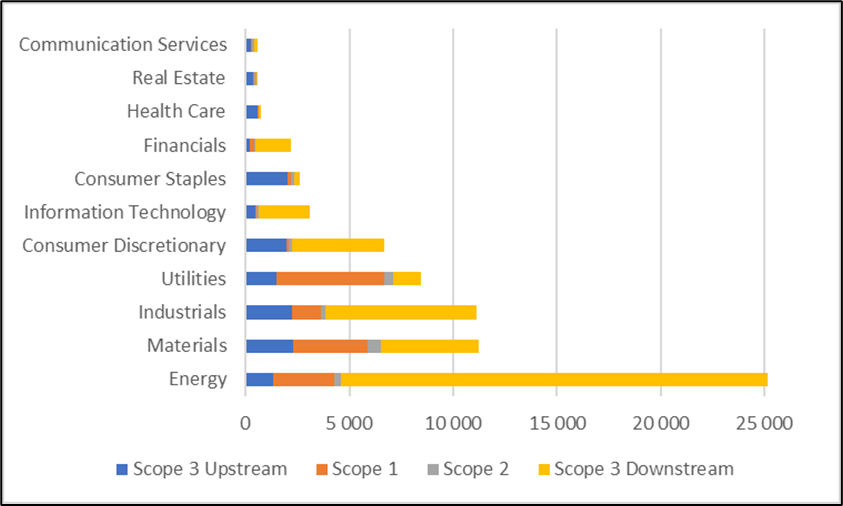

Exhibit 3 helps to explain why the energy transition and climate debate revolves around the same few sectors. Energy, utilities, and materials – suppliers of the basic building blocks of our economies – account for almost two-thirds of all emissions. If all transportation means are added, then the 70% level is easily breached.

Exhibit 3: Absolute emissions by scope and sector (in million tonnes of GHG)

Source: CDP 2019: Full GHG Emissions Dataset, AXA IM

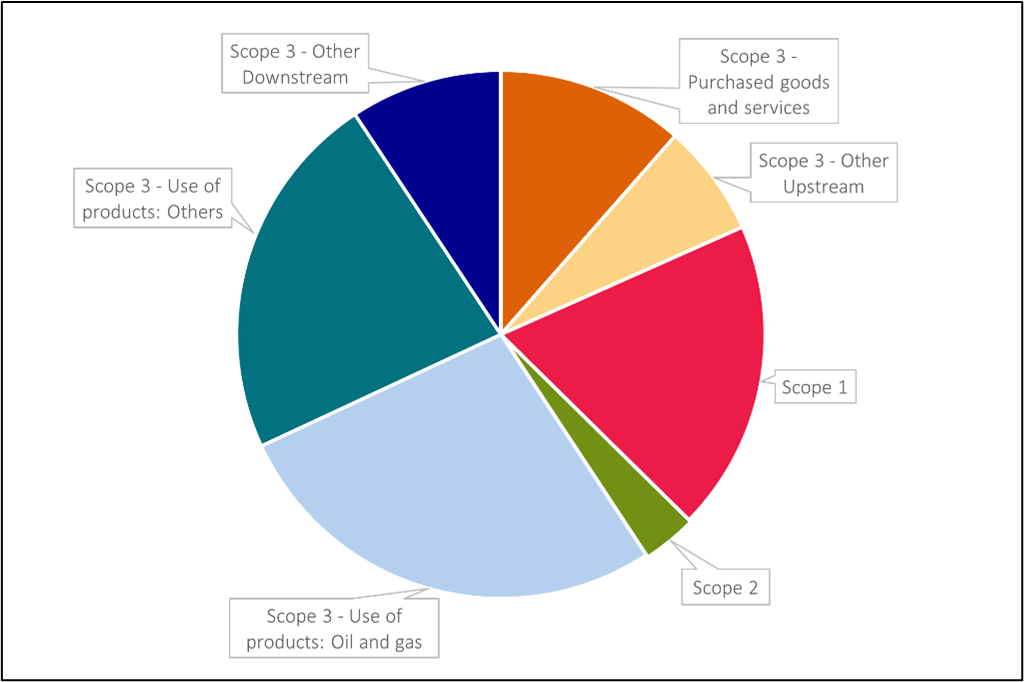

Removing the sector filter and breaking down scope 3, we can see that “use of products” account for 50% of emissions, with the use of oil and gas alone representing 27% of total emissions. The remaining 23% is largely related to selling transportation equipment (from cars to trucks to planes) that themselves consume refined crude oil products, and to all sorts of machinery and electrical equipment that needs fossil fuels or electricity to function.

Exhibit 4: a finer break-down of emissions by scope

Source: “CDP 2019: Full GHG Emissions Dataset”, AXA IM

Availability and quality of data

There is no obligation to publish scope 3 data. Many companies do, and the number is increasing, but many do not.5 This leads to discrepancies in both the availability and the quality of the data, as well as inconsistent coverage across geographies and company sizes. Even for companies that do report scope 3, the coverage is most often partial with only certain sub-categories quantified.6 It is however fair to add that all sub-categories are not applicable or relevant to a given company.

In the CDP dataset we used, 70% of the scope 3 emissions are “cleaned and estimated” by CDP.

Several new initiatives – the European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, India’s Business Responsibility and Sustainability Reporting or new regulations from the US Securities and Exchange Commission7 – should improve the situation by making scope 3 mandatory in reporting. This will however take a few years to be seen in documentation.

Pressure from investors and other stakeholders is another way to improve the situation.

Modeled versus measured

Companies can measure their scope 1 emissions. They can most often count the physical tons of GHGs coming out of their facilities and measure their energy consumption. Scope 1 data – including the scope 1 of electricity producers, i.e. the scope 2 of their clients – are usually reliable and reflect a physical reality.

The contrast is stark with scope 3 data, which very often are not counted but modeled. This applies particularly to downstream emissions and the use and processing of fossil fuels and certain raw materials.

A typical example is the combustion of transportation fuels; the carbon dioxide (CO₂) fumes coming out of each car tailpipe or each plane engine are not measured. They can however be modeled as the quantity of CO₂ generated by burning one liter of gasoline or kerosene is known. In many cases, companies rely on so-called emission factors – coefficients that quantify the emissions per unit of activity.

Although there are many sources for those emission factors, the GHG Protocol provides guidance.8 In addition, CDP has published a technical note for downstream emissions for oil and gas companies that includes emission factors tables.9 French power company TotalEnergies explicitly refers to this note in its scope 3 reporting10

Additionality and multiple counting

Investors should be careful about combining scope 3 data from several companies, as they will be likely to count the same tons more than once. While it makes sense for a given corporate, there are overlaps when many are taken together. For instance, the same ton of CO₂ can be counted in the scope 3 of an independent oil producer, a refiner, a gasoline retailer, and a car manufacturer.

For a portfolio, the level of multiple counting will depend on the diversification across sectors and value chains.

This explains why, in the CDP data set we have mentioned, scope 3 emissions are greater than the world’s GHG emissions.

Flow and stock of emissions

Scope 3 data cover different time horizons. They can relate to a flow – a one-time emission at usage, such as consuming diesel, producing steel or powering up an industrial furnace, or they can relate to a stock of emissions over the lifetime of a product – for instance a car, a plane or a building.

This is a direct result from the “use of sold products” category as some products are long-lived and can generate emissions multiple times. Hence, companies selling products that need fuels or electricity to function – for instance cars, electric machinery, washing machines, but also buildings – will count scope 3 over an agreed lifetime of the product. Companies that sell the fuel or the power will count it only once when it is consumed.

To illustrate this, we can point to the methodology published by global mining company Rio Tinto,11 for “flow scope 3” and by airplane manufacturer Airbus for “stock scope 3” .12 Those are just two examples; many more exist.

Scope 3 and the energy transition: The same thing?

It is deemed best practice for companies to set emissions targets that include scope 3. Indeed, Climate Action 100+, a global investors initiative (of which AXA IM is a member) targeting 166 companies with a large GHG footprint, has designed a benchmark to assess those companies’ climate commitments, including their short-, medium- and long-term scope 3 targets13 14

The United Nations, in a report released during the COP27 climate change conference in Egypt in November 2022, explicitly called for companies to set up net zero targets that include their scope 3 emissions.15

The Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi)16 has published a report to help establish best practice,17 and has issued the following guidelines for companies:

- Set a scope 3 target if scope 3 emissions are greater than 40% of the sum of all three scopes

- This target needs to cover at least two-thirds of scope 3 emissions18

- In a company’s net zero framework, the long-term scope 3 target must cover more than 90% of scope 3 emissions.

These very serious institutions, and many others, are aligned. They consider that it is fair and normal to ask companies to take responsibility for the emissions along their value chain. Whether this is entirely fair has become a moot point. The debate has effectively been settled and companies are now held accountable for all scopes of emissions.

The question remains, however, whether companies can actually do all that much about their scope 3 emissions. It is a matter of influence, control (and lack of control). To go to the heart of the subject: Is it fair to ask for firm targets for scope 3 where a company has at best partial control? What kind of demands should be made? Should we be coldly pragmatic or bullish and ambitious? Should a company be viewed in isolation or as part of our larger society?

Any discussion about scope 3 is fundamentally a discussion about the shape of the energy transition and its practical meaning for companies. For most companies, we have seen that emissions along the value chain are much larger than direct operational emissions, hence reducing them requires an ecosystem change that involves all the participants in the value chain.

And this must happen for all value chains, in all industries. Basically, everyone everywhere will be impacted, and all stakeholders must participate. Investors and asset managers, as owners, have a responsibility to push companies to consider their value chain in their decisions. They are well-positioned to do so thanks to their diversified portfolios. It allows them to see many value chains, identify levers to decarbonize and point at the common levers companies should pull.

The landmark net zero emissions scenario published by the International Energy Agency (IEA) in 2021 makes it very clear that the levers to turn the energy transition into a reality and achieve net zero are all interrelated and interdependent.19

There are many other scenarios – where the contribution of each lever and the outcome are different – to apprehend the energy transition, but they all show this same interdependence. Addressing the scope 1 of the entire economy – hence the scope 3 of companies – is a collective effort. In theory, if everyone everywhere achieves net zero for scope 1, then there are no GHGs emitted anymore and scope 3 is at zero.

Doing nothing is not an option, and any given company has a role to play, but this is a role in a play where the stage is our planet, and the cast its inhabitants. And indeed, the importance of this role varies depending on the climate materiality of products sold and manufactured. Here again, investors have a responsibility. We have seen that a few sectors account for a large majority of emissions. While engaging with companies from those sectors should be a priority, investors should also engage with companies from the entire economy, because everyone has to contribute.

In addition, the lack of availability of bespoke technological solutions is not helping. In its net zero scenario, the IEA reckons that half of the required technologies are not mature enough or even not yet invented.

The true meaning of a corporate ambition for net zero scope 3: Disruption

If investors find a company that states an ambition to achieve net zero scope 3, they should understand that this implies all or some of the following:

- Its entire value chain will be net zero

- The way its products are used will change

- Existing products may be phased out

- It will choose to stop selling certain products

- It will rely on carbon sinks to offset emissions that are not abated.

There are massive implicit and explicit operational, technological, and behavioral bets in such a commitment. There are many companies with a formal net zero ambition that do not know yet how they will achieve it. We welcome an ambition backed by a clear plan, but we must also acknowledge that there are value chains where such a plan cannot yet be mapped out or can only be done partially. For investors, then, the ambition is a signal showing where the company wants to go in the long-term as much as it is a call to arms for areas that can be tackled on a shorter horizon.

What it means industry by industry varies and, while the challenges are enormous for all, they are trickier for some, most notably when the processing or the consumption of the product is the source of GHG emissions.

The case of fossil fuels is the most visible, as burning coal, natural gas and refined oil products is the source of 74% of GHG emissions20 The scope 3 of fossil fuel producers is the scope 1 of all the customers that burn their products. Therefore, for coal miners and for oil and gas producers, net zero scope 3 mostly means that their products are not consumed any more, or emissions are captured and safely stored underground, or they use carbon offsets (potentially at a scale damaging the credibility of their net zero strategy).

To put it differently, in the realm of refined products derived from crude oil, we mostly need technologies allowing us not to burn them or reduce our consumption. To take a familiar case, to get rid of gasoline, we need cars that do not function by burning it.

Another illustration investors can take note of is in the steel value chain. Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon. In a blast furnace, iron ore is reduced to iron through the use of coke – itself made from metallurgical coal – in a process that generates large amounts of CO₂. To a large extent, the cumulative scope 1 of steel producers is the scope 3 of iron ore miners. Companies like Vale, Rio Tinto or BHP – the three largest iron ore producers – can only achieve net zero scope 3 for their iron ore operations if steel making is decarbonized, i.e., if steel companies achieve net zero scope 1.

There are several pathways to do just that, notably capturing the CO₂ or using hydrogen instead of coke. In both cases, the investments are massive. The required process changes occur within steel companies’ operations and outside the iron ore miners’ perimeter. On paper, an iron ore miner could expand its activity to process the iron ore itself – in a decarbonized manner – basically relocating scope 3 into scope 1. It would however be a significant change of business model, that entails making large investments and accepting returns and margins much lower than pure mining.

Another illustration is that all companies, when it comes to upstream scope 3, are concerned by decarbonizing basic materials. Metals, plastics, building materials, glass, paper and wood, ceramics – and the list could be much longer – are everywhere. Any company buying those building blocks of the modern world – be it as raw materials, intermediary parts or manufactured goods – can only be net zero if its suppliers and the suppliers of its suppliers are themselves net zero. In other words, a chain of net zero scope 1 leads to a net zero scope 3 for the entity that sits at the end of the chain.

Those few examples highlight the potential disruptions of value chains through economic and technological choices that are necessary to achieve net zero. Translating net zero targets into the physical world is a capital-intensive reality and will disrupt many business models. For investors, there are companies that provide decarbonization solutions that will have wind in their sails. There are also companies that need to fully change their industrial processes, hence investing large amounts to “only” produce the same products. Disruption can be both an investment opportunity and an investment risk.

A suggested scope 3 engagement roadmap

Into this deeply complex, perhaps intimidating process, responsible investors must find a way to exert their influence as they seek to protect portfolios from risk and foster long-term sustainable economies. We believe that in any engagement around this issue, a balance has to be struck between ambition and pragmatism.

We find that it is too easy for investors to ask a company to commit to net zero scope 3 and brush aside the related challenges of doing so. By the same token, it is too easy for a company to brush aside its role in the energy transition by claiming that this is all about customer choices and not its responsibility.

While the complexity of moving entire value chains should not be underappreciated and ignored when engaging with companies, it should not lead to a free pass. If engaging on scope 1 and 2 is straightforward, we believe that engaging on scope 3 demands more nuance.

Engaging on scope 1 and 2: No negotiation. Companies are responsible for their direct emissions. It does not mean that this is easy or that the economic and technological maturity is there, but companies must have emissions reduction targets and a genuine plan – covering investments and governance – to achieve them.

Engaging on scope 3: More nuance. We believe that the complexity of scope 3 does not allow us to address it from a single vantage point or with one set of tools.

We believe that a scope 3 engagement should be broken down into several parts:

- Hard commitments for controllable scope 3 emissions. Controllable scope 3 may appear as an absurd idea, but there are a few domains where a company actually controls or can control those emissions. These could include, for example, a company that is the sole purchaser of a component manufactured by a supplier or a franchisor than can dictate operational terms to its franchisees

- Strong commitments for “influenceable” scope 3 emissions. Many large companies have an oversized influence on part of their value chain. They have muscles that they can flex to help reduce emissions, not just to cut a better deal. Typically, they can engage with their suppliers and ask them to have their own decarbonization plans, especially for small- and medium-sized suppliers that may not have their own sustainability goals.They can push for better practices and promote strong standards; this is for instance the case for large food companies that buy agricultural raw ingredients from tens of thousands of farmers. They can also select logistic partners on their carbon efficiency. For instance, for trucking, favor partners with a modern and efficient fleet. There are many more examples of this kind

- Address and discuss non-controllable scope 3 emissions. While there may be a lack of control, it does not mean that those emissions should be ignored. We expect companies to explain the situation, present the potential pathways to decarbonize – notably downstream – and highlight what they can do today and could do in the future as new technologies become available. This applies very clearly to the use and processing of sold products.

Basically, we want companies to contribute to shifts in the ecosystem. For instance, we would want to understand how a fuel retailer contributes to the development of charging infrastructure for electric vehicles.

AXA IM is a member of the Net Zero Asset Managers initiative (NZAMI) and we are committed to achieve net zero for our investments. This implies that companies we invest in must have today or should have fairly soon a broad net zero ambition. This ambition must absolutely cover scope 1 and 2 emissions. And while scope 3 is more complex, it should be part of the ambition, possibly at a limited level initially, but with the clear aspiration to achieve full coverage in time.

- V2hhdCBpcyBHSEcgUHJvdG9jb2w/IEdyZWVuaG91c2UgR2FzIFByb3RvY29sLCBGZWJydWFyeSAyMDIz

- VGhlcmUgaXMgYW5vdGhlciBidWNrZXQsIGluZm9ybWFsbHkgY2FsbGVkIHNjb3BlIDQsIHRoYXQgd291bGQgcmVsYXRlIHRvIOKAmGF2b2lkZWQgZW1pc3Npb25z4oCZLiBUaGUgaWRlYSBpcyB0aGF0IGEgY29tcGFueSBtaWdodCBnYWluIGNyZWRpdCBmb3IgR0hHcyBub3QgZW1pdHRlZCB0aGFua3MgdG8gdGhlIHVzZSBvZiBhIGdpdmVuIHByb2R1Y3Qgb3Igc2VydmljZS4gQXQgdGhpcyBzdGFnZSwgdGhlcmUgaXMgbm8gc3RhbmRhcmQgYW5kIG5vIGJyb2FkIG1ldGhvZG9sb2d5IGZvciBzY29wZSA0Lg==

- MjAyMCBkYXRhIGFyZSBhdmFpbGFibGUsIGJ1dCB3ZSBjaG9zZSB0aGUgZmluYWwgcHJlLXBhbmRlbWljIHllYXIuIFRoZSBDRFAgcnVucyB0aGUgd29ybGQgZW52aXJvbm1lbnRhbCBkaXNjbG9zdXJlIHN5c3RlbSBhbmQgaXMgZnVuZGVkIGJ5IGEgY29tYmluYXRpb24gb2YgcGhpbGFudGhyb3B5LCBtZW1iZXJzaGlwIGZlZXMgYW5kIGdvdmVybm1lbnQgZ3JhbnRzLg==

- SGlzdG9yaWNhbCBHSEcgRW1pc3Npb25zLCBXb3JsZCBSZXNvdXJjZXMgSW5zdGl0dXRlLCByZXRyaWV2ZWQgRmVicnVhcnkgMjAyMw==

- UmVwb3J0ZWQgRW1pc3Npb24gRm9vdHByaW50czogVGhlIENoYWxsZW5nZSBpcyBSZWFsLCBNU0NJLCBNYXJjaCAyMDIy

- U2NvcGUgMyBDYXJib24gRW1pc3Npb25zOiBTZWVpbmcgdGhlIEZ1bGwgUGljdHVyZSwgTVNDSSwgU2VwdGVtYmVyIDIwMjA=

- U0VDIFByb3Bvc2VzIFJ1bGVzIHRvIEVuaGFuY2UgYW5kIFN0YW5kYXJkaXplIENsaW1hdGUtUmVsYXRlZCBEaXNjbG9zdXJlcyBmb3IgSW52ZXN0b3JzLCBTRUMsIE1hcmNoIDIwMjI=

- Q2F0ZWdvcnkgMTE6IFVzZSBvZiBTb2xkIFByb2R1Y3RzLCBHSEcgUHJvdG9jb2wsIHJldHJpZXZlZCBGZWJydWFyeSAyMDIz

- Q0RQIFRlY2huaWNhbCBOb3RlOiBHdWlkYW5jZSBtZXRob2RvbG9neSBmb3IgZXN0aW1hdGlvbiBvZiBTY29wZSAzIGNhdGVnb3J5IDExIGVtaXNzaW9ucyBmb3Igb2lsIGFuZCBnYXMgY29tcGFuaWVzLCBDRFAsIEphbnVhcnkgMjAyMg==

- VG90YWxFbmVyZ2llc19Vbml2ZXJzYWwgUmVnaXN0cmF0aW9uIERvY3VtZW50IDIwMjE=

- Q2xpbWF0ZSBDaGFuZ2UsIFJpbyBUaW50bywgcmV0cmlldmVkIEZlYnJ1YXJ5IDIwMjM=

- VW5pdmVyc2FsIFJlZ2lzdHJhdGlvbiBEb2N1bWVudCAyMDIxLCBBaXJidXMsIDIwMjE=

- TWV0aG9kb2xvZ2llcyB8IENsaW1hdGUgQWN0aW9uIDEwMCs=

- TmV0IFplcm8gQ29tcGFueSBCZW5jaG1hcmssIENsaW1hdGUgQWN0aW9uIDEwMCssIHJldHJpZXZlZCBGZWJydWFyeSAyMDIz

- SW50ZWdyaXR5IE1hdHRlcnM6IE5ldCBaZXJvIENvbW1pdG1lbnRzIGJ5IEJ1c2luZXNzZXMsIEZpbmFuY2lhbCBJbnN0aXR1dGlvbnMsIENpdGllcyBhbmQgUmVnaW9ucywgVW5pdGVkIE5hdGlvbnMsIE5vdmVtYmVyIDIwMjI=

- VGhlIFNCVGkgaXMgYSB0aGlyZC1wYXJ0eSBwcm92aWRlciB3aGljaCBjaGVja3MgYW5kIGFwcHJvdmVzIGNvbXBhbnkgdGFyZ2V0cyBhZ2FpbnN0IFBhcmlzIEFncmVlbWVudCBzY2VuYXJpb3M=

- VmFsdWUgQ2hhbmdlIGluIFRoZSBWYWx1ZSBDaGFpbjogQmVzdCBQcmFjdGljZXMgaW4gU2NvcGUgMyBHcmVlbmhvdXNlIEdhcyBNYW5hZ2VtZW50LCBTQlRpLCBOb3ZlbWJlciAyMDE4

- VGhpcyBtYXkgbWVhbiB0aGF0IGNvbXBhbmllcyB3aXRoIGEgbGFyZ2Ugc2NvcGUgMyBmcm9tIHRoZSBwcm9jZXNzaW5nIG9yIHVzZSBvZiB0aGUgcHJvZHVjdHMgdGhleSBzZWxsIChzdWItY2F0ZWdvcnkgMTAgYW5kIDExIG9mIHNjb3BlIDMpIG1heSBiZSB1bmFibGUgb3IgdmVyeSBjaGFsbGVuZ2VkIHRvIHN1Ym1pdCB0YXJnZXRzIHRvIFNCVGksIGFzIHRoZXkgaGF2ZSBubyBvciBsaW1pdGVkIGNvbnRyb2wgb3ZlciB0aG9zZSBkb3duc3RyZWFtIGVtaXNzaW9ucw==

- VGhlIElFQeKAmXMgcGF0aCB0byBuZXQgemVybywgQVhBIElNLCBKdW5lIDIwMjE=

- V29ybGQgR3JlZW5ob3VzZSBHYXMgRW1pc3Npb25zIGluIDIwMTkgYnkgU2VjdG9yLCBFbmQgVXNlIGFuZCBHYXNlcyAoc3RhdGljKSwgV29ybGQgUmVzb3VyY2VzIEluc3RpdHV0ZSwgcmV0cmlldmVkIEZlYnJ1YXJ5IDIwMjM=

Disclaimer

Not for Retail distribution: this document is intended exclusively for Professional, Institutional, Qualified or Wholesale Investors / Clients, as defined by applicable local laws and regulation. Circulation must be restricted accordingly.

This document is being provided for informational purposes only. The information contained herein is confidential and is intended solely for the person to which it has been delivered. It may not be reproduced or transmitted, in whole or in part, by any means, to third parties without the prior consent of the AXA Investment Managers, Inc. (the “Adviser”). This communication does not constitute on the part of AXA Investment Managers a solicitation or investment, legal or tax advice. Due to its simplification, this document is partial and opinions, estimates and forecasts herein are subjective and subject to change without notice. There is no guarantee forecasts made will come to pass. Data, figures, declarations, analysis, predictions and other information in this document is provided based on our state of knowledge at the time of creation of this document. Whilst every care is taken, no representation or warranty (including liability towards third parties), express or implied, is made as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of the information contained herein. Reliance upon information in this material is at the sole discretion of the recipient. This material does not contain sufficient information to support an investment decision.

© 2023 AXA Investment Managers. All rights reserved